Socio-economic context

A strong agricultural centre and a diverse social context

The Upper Paranapanema Basin is predominantly rural, with agriculture central to jobs and land value, and clear differences in economic and social conditions between municipalities.

Current situation

Research insights

Current situation

Economic situation

The Upper Paranapanema Basin is a largely rural region whose economy depends on natural resources such as land and water. Although it covers more than 10% of the territory of São Paulo State, the basin contributes a relatively small share of the state’s total economic output, which is less than 1% of state GDP.

Economic activity is unevenly distributed, with more than half of the basin’s GDP generated by a small group of municipalities, including centres such as Itapetininga, Avaré, Itapeva and Capão Bonito.

The GDP of the Basin represents approximately R$ 17 million (0.9% of the state), with the following sectors: Services 67.6%; Industry 15.7%; Agriculture 16.8%.

Agriculture plays a much larger role in the basin’s economy than it does at the state level. While agriculture accounts for less than 2% of value added statewide, in the Upper Paranapanema it contributes between 5% and 40% of municipal value added, depending on the municipality.

The sector is also a major source of employment: agriculture represents 6% to 55% of formal jobs across basin municipalities, compared with around 3% statewide.

Services remain the largest contributor to GDP overall, but agriculture and forestry are important drivers of local economic activity and land value in the basin.

The basin is home to cultivation of cereals, soybeans, cotton, apples, pears, peaches, grapes, potatoes, tomatoes, beans, peas, forestry, as well as the raising of pigs, buffalo, and traíra (a type of fish).

Agriculture dominates the economy in the Basin.

Sociological situation

The Upper Paranapanema Basin is a predominantly rural and agricultural region. In 2020, it was home to just over 760,000 people, less than 2% of São Paulo State’s population.

Its social structure and livelihoods are closely connected with land and water use, with agriculture forming a central part of local economies and daily life. Agriculture has historically dominated land use and economic activity, shaping settlement patterns, family structures, and local labour markets.

Social conditions in the basin reflect a mix of relative strengths in basic development and disparities in economic opportunity. While many municipalities in rural regions like this can show medium–high human development scores (such as those captured by IDH/IDHM at broader scales), they also tend to score lower on social responsibility and wealth indices like the IPRS, which capture income, access to services, and economic resources more directly. This pattern suggests that while access to education and basic services may be reasonably established, income levels, job diversity, and economic resilience remain limited relative to more urbanised parts of the state. Income gaps

and variations in quality of life indicators, including health and access to infrastructure, are shaped by differences in access to land, capital, water, and markets, with agriculture remaining a major, but unevenly rewarded, source of economic activity.

In the Upper Paranapanema Basin, agriculture shapes social life and livelihoods, but gaps in income and opportunity reflect broader patterns of rural inequality and limited economic diversification.

Research insights

xx

Rapid growth of irrigation

Agriculture in the Upper Paranapanema Basin has become increasingly dependent on the intensive use of natural resources, particularly water.

A key driver of this shift has been the expansion of central pivot irrigation, which has made large-scale, irrigated cropping possible across much of the region.

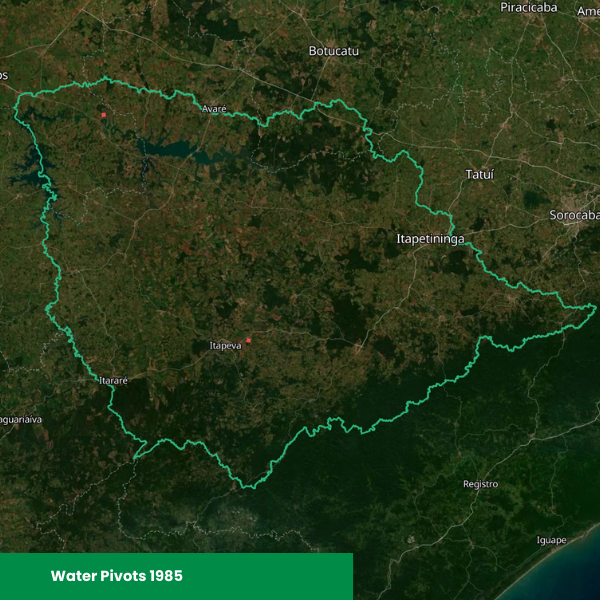

In the 1980s, there were only three systems operating in the basin. Since then, the number of pivots has grown sharply. Data from the National Water Agency shows that there were around 1,670 systems in 2014, rising to more than 2,300 by 2022. Municipalities with the largest irrigated areas include Itaí, Paranapanema, Itapeva, Itaberá, and Buri.

This expansion reflects the growth of export-oriented crops,

particularly soybean and maize, and the increasing corporate nature of agricultural production. Installing and operating a central pivot system requires significant capital investment, which is typically beyond the reach of individual family farmers. As a result, irrigation-led modernisation has reinforced the trend of declining family farming alongside the expansion of larger, more capitalised and competitive agricultural operations.

The number of water pivots has increased significantly since the first ones were installed in the 1980s.

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

How has irrigation expanded in the Alto Paranapanema region, and what does this reveal about changing patterns of land and water use?

Data sources

National irrigation and water-use records (including data from the Agência Nacional de Águas – ANA)

Agricultural census and regional land-use data

Municipal-level irrigation infrastructure records

Historical land-use mapping (remote sensing)

Methods

Compilation of historical and recent data on central pivot irrigation systems

Temporal comparison of irrigation presence from the 1980s to the 2010s–2020s

Spatial analysis of irrigation concentration across municipalities in the Upper Paranapanema Basin

Key quantitative results

In the 1980s, only three central pivot irrigation systems were operating in the region.

By 2014, the number of central pivots had increased to approximately 1,670 systems.

By 2022, this number had surpassed 2,300 systems, indicating very rapid expansion over four decades.

Municipalities with the largest irrigated areas include Itaí, Paranapanema, Itapeva, Itaberá, and Buri.

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial scale: Upper Paranapanema Basin, with analysis at the municipal level.

Temporal scale: Long-term change from the 1980s to 2022, capturing the transition from minimal irrigation to widespread adoption.

Reference publications

Santos, L. L., Graciano, M. C., Araujo, J. C. L., Melo, D. P., & Martensen, A. C. (2023).

Agronegócio e a busca por terra e água: uso do solo, irrigação e estrutura fundiária na Região do Alto Paranapanema – São Paulo.

xx

Declining numbers of family farms and increasing land concentration

In the Upper Paranapanema Basin, the number of family farming establishments has been declining, contributing to a broader process of land concentration. Under Brazilian Law No. 11,326 (2006), a family farmer is defined as a producer who operates no more than four fiscal modules of land, relies primarily on family labour, and derives most household income from activities carried out on the rural property.

Analysis by Santos et al. (2023) shows that between 2006 and 2017, the total number of family farming establishments in the basin declined overall, despite some short-term fluctuations. Twenty-two municipalities recorded reductions of more than 20%, seven municipalities experienced declines of 10–20%, and a further two municipalities saw losses of 5–10% in the number of family farms. This contraction occurred alongside a significant expansion in the area under intensified agriculture, indicating that agricultural land has increasingly shifted toward larger, more capitalised production units.

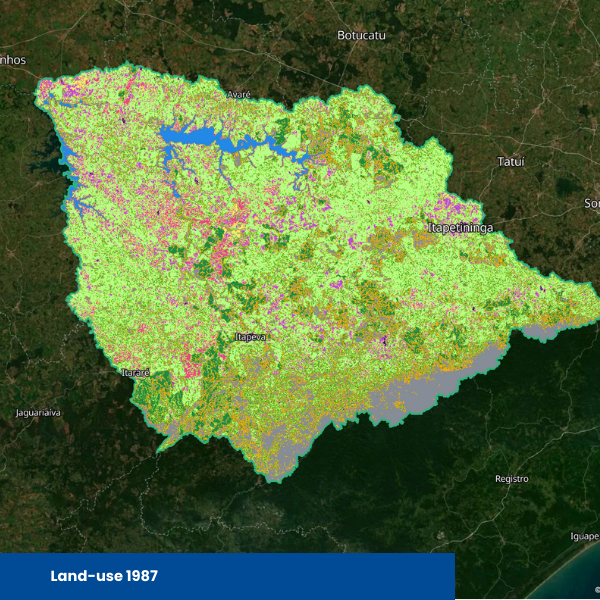

Over the same period, Santos et al. document a substantial increase in land dedicated to intensified agricultural systems, with intensified agriculture expanding by approximately 600% between 1987 and 2017, largely replacing pasturelands. This expansion was closely associated with the growth of mechanised and irrigated cropping systems, reinforcing a pattern in which fewer establishments control a larger share of agricultural land. Taken together, these trends show that agricultural production in the basin has increased in area and intensity, even as the number of family farming operations has declined.

The area of the Basin used for agriculture is increasing

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

How has the structure of agricultural land ownership changed in the Alto Paranapanema Basin over recent decades?

What is the relationship between the decline in family farming establishments and the expansion of intensified agriculture in the basin?

How has the total area under agricultural production changed as the number of farming establishments has declined?

Data sources

Cartographic data on land use and central-pivot irrigation in the Upper Paranapanema Basin across different periods between the 1980s and the 2010s, produced by the Center for Studies in Spatial Ecology and Sustainable Development (Núcleo de Estudos em Ecologia Espacial e Desenvolvimento Sustentável - NEEDS).

Data on changes in the number of family farming establishments in the Upper Paranapanema region between 2006 and 2017, obtained from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE).

Census data from the LU-PA Project (Census Survey of Agricultural Production Units) of the São Paulo State Secretariat of Agriculture and Supply and the Institute of Agricultural Economics.

Methods

Analysis of cartographic data to assess changes in land use and the adoption of central-pivot irrigation in the Upper Paranapanema Basin.

Production of maps to represent changes in the number of family farming establishments in the region.

Integration and spatial analysis of Gini indices of land distribution calculated for the 44 municipalities in the region.

Key quantitative results

Land use: Between 1987 and 2017, land use changed markedly, with agricultural expansion over areas previously dominated by pasture, which were strongly reduced.

Family farming: The number of family farming establishments declined in 31 of the 44 municipalities between 2006 and 2017.

Land concentration: Most municipalities showed medium to high levels of land concentration, with an intensification of this process in about 75% of municipalities between 1995 and 2017.

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial scale: Upper Paranapanema region, comprising 44 municipalities within the Paranapanema River basin.

Temporal scale: From the late 1980s to 2017.

Reference publications

Santos, L. L., Graciano, M. C., Araujo, J. C. L., Melo, D. P., & Martensen, A. C. (2023).

Agronegócio e a busca por terra e água: uso do solo, irrigação e estrutura fundiária na Região do Alto Paranapanema – São Paulo.

xx

Landowner attitudes to nature recovery

With close to a third of Brazil’s land used for agriculture, farmers are critical actors in any large-scale nature recovery effort. In the Upper Paranapanema Basin, nature recovery is most effective when it is integrated into existing agricultural systems rather than imposed as land set aside from production.

Evidence shows that regulation alone is unlikely to deliver sustained restoration outcomes. Landowners respond more positively when nature recovery is supported by clear legal frameworks, financial incentives, technical assistance, and flexible restoration models such as agroforestry or natural regeneration. These approaches reduce perceived risk, align restoration with farm productivity, and increase willingness to participate, especially among smaller landholders. Catchment-scale programmes and payments for ecosystem services are particularly important for enabling broader participation and long-term commitment.

Farmers play a central role in nature recovery, but participation depends on incentives, support, and how well restoration fits within existing agricultural practices.

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

What factors influence landowner decisions to retain or restore native vegetation?

How do farm resources, capacity, and landscape characteristics shape restoration outcomes?

How do different policy approaches affect landowner motivation and compliance?

Data sources

Land-use and land-cover datasets for São Paulo State

Farm structure and property size data

Spatial data on slope and land suitability

Surveys of farmer behaviour and perceptions

Policy and regulatory context, including the Brazilian Forest Code

Methods

Statistical analysis linking farm characteristics and landscape features to forest cover

Comparison of restoration outcomes across property sizes and land-use types

Assessment of policy instruments and their influence on landowner behaviour

Integration of socio-economic, spatial, and environmental variables

Key quantitative results

Larger farms, used as a proxy for greater access to capital and resources, are associated with higher levels of forest cover.

Steeper slopes, which are less suitable for intensive agriculture, are also associated with increased forest retention and regeneration.

Reliance on punitive policy tools alone, such as fines, is associated with weaker landowner engagement.

Positive incentives and technical support are linked to improved compliance and more durable restoration outcomes.

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial scale: State of São Paulo, with findings applicable to agricultural regions including the Upper Paranapanema Basin.

Temporal scale: Analysis spans multiple years of land-use and policy data, capturing medium-term trends in restoration and landowner behaviour.

Reference publications

Nardy, J. R., Duden, A., Martensen, A. C., Henkens, K., Verweij, P., & Verburg, R. (2025).

The role of farmers’ resources, capabilities and perceptions on reforestation and forest cover in the Atlantic Forest.

Land Use Policy, Volume 154, 2025

Duden, A. S., Verweij, P. A., Martensen, A. C., & Verburg, R. W. (2025).

Drivers of reforestation across land-use sectors in the State of São Paulo,

Brazil. Land Use Policy, Volume 150, 2025

Santos, L. L., Graciano, M. C., Araujo, J. C. L., Melo, D. P., & Martensen, A. C. (2023).

Agronegócio e a busca por terra e água: uso do solo, irrigação e estrutura fundiária na Região do Alto Paranapanema.