Environmental context

A unique and threatened environment

The Upper Paranapanema Basin is a landscape of contrasts.

It contains some of the largest remaining remnants of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest alongside highly degraded agricultural areas affected by erosion, water stress, and biodiversity loss.

Located at the edges of the Atlantic Forest and the Cerrado, the basin supports high biodiversity and plays a critical role in water regulation and landscape connectivity.

Over recent decades agricultural expansion and intensification, and expansion of irrigation have placed growing pressure on soils, rivers, ecosystems, and rural livelihoods.

These overlapping environmental and socio-economic pressures make the basin both high risk and high opportunity.

With targeted restoration and improved land-use management (particularly along waterways) the Upper Paranapanema has the potential to become a model for balancing agricultural production, water security, and nature recovery at a landscape scale.

Current situation

Research insights

Current situation

Native vegetation

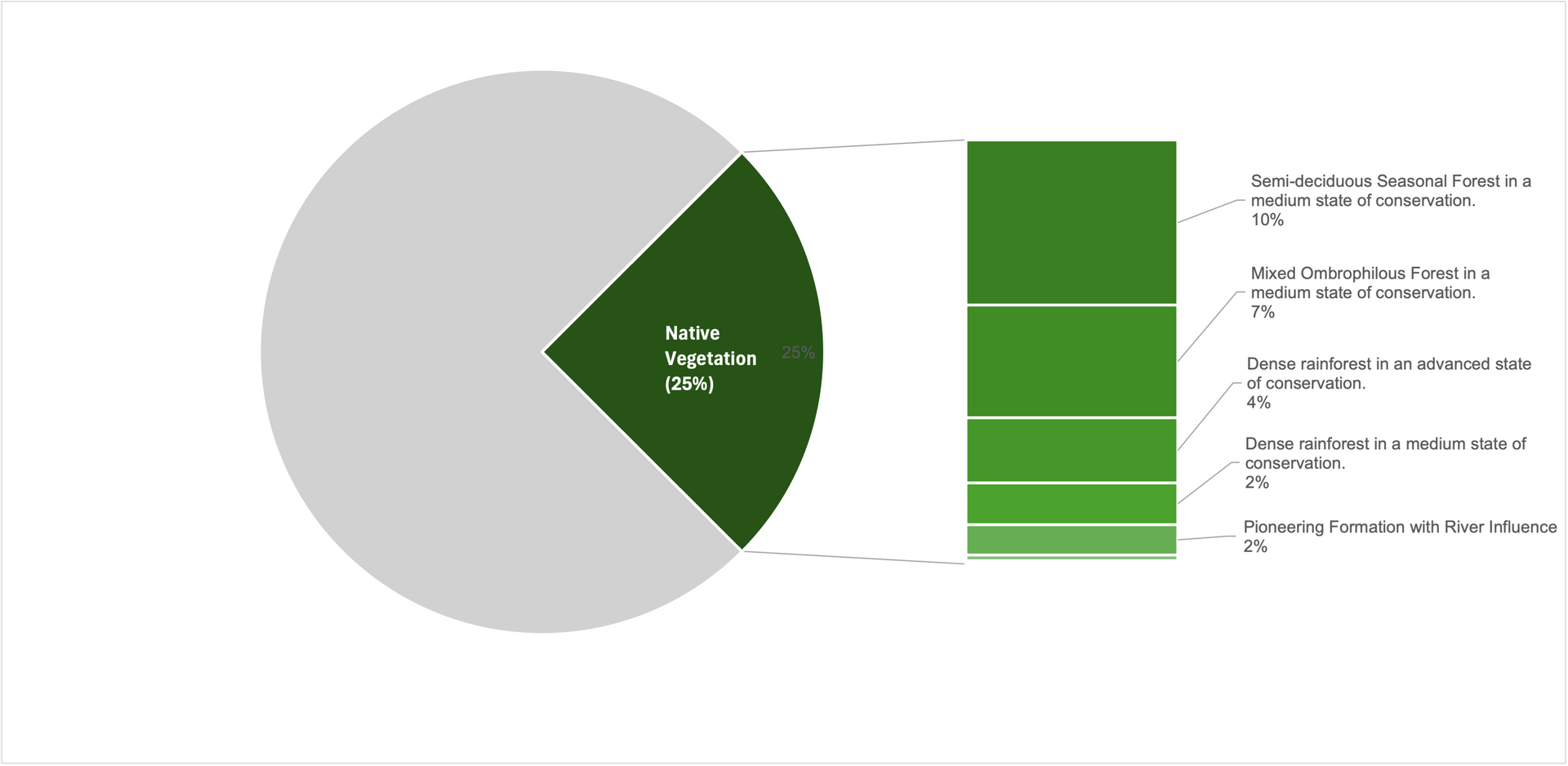

The total area of the Upper Paranapanema Basin is close to 2.3 million hectares, with a quarter covered by native vegetation. Native vegetation cover varies between municipalities, ranging from close to 50% in Bom Sucesso de Itararé down to 8.5% in Arandu.

Native vegetation covers around a quarter of the Upper Paranapanema Basin.

Species present

The Upper Paranapanema Basin is home to a wide range of Atlantic Forest plants and animals. This reflects its position within the Serra de Paranapiacaba forest landscape and the mix of habitats found across the basin, including large areas of forest, river corridors, and transition-zone environments.

Key species groups include:

Large and medium-sized mammals

The region supports forest-dependent mammals typically found in well-preserved Atlantic Forest landscapes. This includes wide-ranging and threatened species such as jaguars, pumas, South American tapirs, bush dogs, southern muriquis, and native deer. These animals rely on large areas of connected habitat and are strong indicators of overall ecosystem health.

Birds

Bird life in the basin is highly diverse, with species associated with intact forests, river edges, and transition habitats. Many Atlantic Forest bird species are sensitive to habitat condition, making them useful indicators of ecosystem health and the success of restoration efforts.

Amphibians and other water-dependent species

Streams, wetlands, and riparian forests support amphibians and other species that depend on clean, well-regulated water. The presence of rare and range-restricted amphibians highlights the importance of headwaters and streamside habitats for conservation.

Plants and vegetation

Native vegetation includes dense montane Atlantic Forest, bamboo-rich forest types, riparian forests along waterways, and smaller areas of high-altitude vegetation. This variety of plant communities creates a diverse set of habitats that supports high species richness across the basin.

The Upper Paranapanema Basin supports Atlantic Forest wildlife, including large mammals and water-dependent species that rely on connected forests and rivers.

Environmental values

Biodiversity in the Upper Paranapanema Basin underpins a set of high-value environmental attributes that are critical at both basin and state scales.

Key environmental values include:

Strategic water sources

The basin contains important headwaters and spring systems that contribute to regional water supply, making forest protection directly relevant to water security.

Landscape connectivity

Large forest blocks, riparian corridors, and remaining forest fragments collectively support ecological connectivity across the landscape, enabling species movement and genetic exchange.

Soil stability and catchment protection

Native vegetation plays a major role in stabilising soils, reducing erosion, and limiting sedimentation in rivers, particularly important in an agriculturally intensive basin.

Ecological resilience

The coexistence of multiple habitat types increases the basin’s ability to absorb and recover from environmental stressors such as drought, floods, and land-use change.

Forests, rivers, and headwaters in the basin protect water security, stabilise soils, and strengthen the resilience of the whole landscape.

Ecosystem services

The species and environmental features of the Upper Paranapanema Basin provide a wide range of ecosystem services that support farming, communities, and downstream water users. The following services have been classified using the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment framework for ecosystem services.

Provisioning services

Provisioning services are tangible products or resources that people can obtain directly from nature including:

- Freshwater supply for households, irrigation, and industry, drawn from rivers, springs, and aquifers maintained by forests and headwaters

- Food production including crops and livestock supported by fertile soils and favorable climate

- Fish and aquatic resources from rivers and reservoirs throughout the basin

- Timber and fuelwood from both native Atlantic Forest remnants and planted forests

- Medicinal plants and genetic resources from the region's rich biodiversity

- Fiber and fodder for livestock and various agricultural uses

Regulating services

Regulating services deliver benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes:

- Water purification through natural filtration, nutrient uptake by vegetation, and buffering of pollutants before they reach waterways

- Water flow regulation including groundwater recharge, maintenance of river flows during dry periods, and buffering of seasonal variability

- Flood regulation through water retention in forests, wetlands, and soils, reducing peak flows and protecting downstream communities

- Erosion control and sediment retention by vegetation and root systems, reducing damage to rivers, reservoirs, and infrastructure

- Pollination by native insects and other animals, supporting both wild plant reproduction and agricultural productivity

- Pest and disease regulation through natural predators and ecosystem balance, reducing agricultural losses

- Climate regulation at local and regional scales, moderating temperature and moisture extremes

- Carbon sequestration and storage, especially in mature Atlantic Forest vegetation and soils

Cultural and indirect services

Cultural services provide non-material benefits that contribute to human wellbeing and quality of life:

- Recreation and ecotourism opportunities in forests, rivers, and reservoirs, supporting local economies

- Aesthetic and spiritual values derived from natural landscapes, waterfalls, and forest environments

- Scientific research and environmental education, improving understanding and management of natural systems

- Cultural heritage and regional identity linked to forests, rivers, and traditional land use practices

- Sense of place connecting communities to their landscape and history

Supporting services

Supporting services are foundational ecological processes that underpin all other ecosystem services:

- Nutrient cycling through decomposition and biological processes, which underpin long-term land productivity

- Soil formation and maintenance through weathering, organic matter accumulation, and biological activity

- Primary production by plants, converting solar energy into biomass that supports all food webs

- Habitat provision for native species and pollinators, supporting biodiversity and ecosystem balance

- Landscape connectivity allowing species to move and ecosystems to function over time

Natural processes regulate water quality and flow, control floods and erosion, support pollination and pest control, and moderate climate while storing carbon.

Research insights

Forest cover and fragmentation

Native vegetation in the basin ranges from large, continuous forest areas, such as the Serra de Paranapiacaba ecological continuum, the largest remaining Atlantic Forest block in Brazil, to highly fragmented landscapes dominated by small forest patches.

Despite their size and isolation, these fragments retain a significant proportion of the region’s original biodiversity, demonstrating their continued ecological value.

Land use, ecosystem condition, and environmental pressures vary markedly across the region, creating a mosaic of conserved and degraded areas with different risks and restoration needs.

This reflects long-term land use change and uneven conservation outcomes across municipalities, resulting in extremes of preservation and degradation within the same basin.

83% of all remaining Atlantic Forest fragments are smaller than 50 hectares

45–50% of forest fragments are smaller than 10 hectares

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

What is the size distribution, spatial configuration, and connectivity of remaining native vegetation fragments, and how does this relate to biodiversity persistence?

Data sources

- Landsat-derived land-cover maps for the Atlantic Forest biome

- São Paulo State vegetation maps

- Fragment polygons extracted from classified forest cover datasets

Methods

Forest fragments were delineated from classified land-cover rasters.

Fragment size classes were calculated using GIS-based polygon analysis.

Connectivity metrics were derived using distance-based and graph-based approaches.

Bird species richness and abundance were modelled as a function of:

- forest cover (%)

- fragment size (ha)

- connectivity indices

Key quantitative results

~45–50% of forest fragments are <10 ha

~83% of fragments are <50 ha

Small fragments still contribute significantly to species richness when embedded in connected landscapes

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial: Atlantic Forest biome; São Paulo State; regional subsets applicable to Alto Paranapanema

Temporal: Forest cover based on late-20th to early-21st century satellite imagery

Reference publications

Ribeiro, M.C., Metzger, J.P., Martensen, A.C., Ponzoni, F.J., & Hirota, M.M. (2009).

The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: How much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed?

Biological Conservation

Ribeiro, M.C., Martensen, A.C., Metzger, J.P., Scarano, F.R., & Fortin, M.J. (2011).

The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: A shrinking biodiversity hotspot.

Biodiversity Hotspots: Distribution and Protection of Conservation Priority Areas. Springer

Martensen, A.C., Ribeiro, M.C., Banks-Leite, C., Prado, P.I., & Metzger, J.P. (2012).

Associations of forest cover, fragment area, and connectivity with Neotropical understory bird species richness and abundance

Conservation Biology

Biome transition region

The Upper Paranapanema lies at the interface between the Atlantic Forest and the Cerrado, creating a mosaic of landscapes shaped by climate, soils, and hydrology. This transition zone supports species from multiple biomes which increases biodiversity, but also heightens species sensitivity to habitat loss and fragmentation.

Research shows that species respond differently to habitat loss depending on their position within geographic ranges. This indicates that conservation and restoration in transition regions can be particularly important for maintaining populations at range edges.

Because the Alto Paranapanema lies within a major Atlantic Forest–Cerrado transition, a higher proportion of species occur near their range limits. This means that nature improvements in this basin may have higher biodiversity impacts relative to similar levels of habitat improvement in biome core areas.

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

How do species populations respond to habitat loss and fragmentation in ecological transition zones, and what are the implications for conservation and restoration strategies in regions where biomes overlap?

Data sources

- Species occurrence and abundance data for multiple bird species across their geographic ranges

- Spatial land-cover and habitat-loss datasets derived from remote sensing

- Fragmentation metrics calculated at multiple spatial scales

Methods

Species populations were analysed across their entire distribution ranges, not only within core habitat areas.

Habitat loss and fragmentation metrics were quantified spatially and linked to population responses using statistical models.

Comparisons were made between:

- core range populations

- edge-of-range populations (typical of transition zones)

Models assessed whether sensitivity to habitat loss differed depending on a population’s position within a species’ range.

Key quantitative results

Population responses to habitat loss are not uniform across a species’ range.

Populations located at range edges — common in transition regions — often show greater sensitivity to habitat loss and fragmentation.

Habitat loss in transition zones can therefore have disproportionate impacts on regional and species-level persistence compared to equivalent loss in core areas.

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial scale: Broad, multi-regional analyses across species’ distribution ranges, including transition zones such as Atlantic Forest–Cerrado interfaces

Temporal scale: Contemporary habitat-loss patterns based on recent land-cover datasets

Limitations and uncertainties

Results are based on bird species, which are mobile and relatively well studied; responses may differ for plants, amphibians, or invertebrates.

Sensitivity to habitat loss may vary by species traits (e.g. dispersal ability, habitat specialisation).

Transition zones are ecologically complex; biome boundaries are often diffuse rather than discrete.

Reference publications

Hasui, E. et al. (2024).

Populations across bird species distribution ranges respond differently to habitat loss and fragmentation.

Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation

Compliance with environmental laws

Permanent Preservation Areas (PPAs) are a central mechanism in Brazilian environmental law for protecting water resources, soils, biodiversity, and ecological connectivity on private land. In Southwestern São Paulo, a large share of these areas—especially along rivers and streams—are currently degraded and out of legal compliance, creating significant environmental liabilities for rural properties.

Approximately 155,000 hectares of riparian PPAs exist in the region, and nearly half are degraded. Large rural properties dominate the landscape and therefore hold most of the total area of PPAs requiring restoration. However, smaller properties show a higher proportion of degradation, meaning they are often less compliant despite having less land overall. This imbalance has important implications for policy design, as compliance costs fall unevenly across landholders.

Restoring PPAs is critical not only for legal compliance but for water security and landscape connectivity. Riparian PPAs link small forest fragments to major forest blocks, including the Serra de Paranapiacaba ecological continuum, and play a key role in maintaining water quality and regulating flows in a highly farmed landscape. Yet restoration costs are substantial, estimated at USD 76–100 million across the study area. Without financial incentives, payments for ecosystem services, or lower-cost restoration approaches (such as agroforestry and natural regeneration), many landholders (particularly smallholders) are unlikely to be able to meet their legal obligations.

Nearly half of riparian Permanent Preservation Areas in Southwestern São Paulo are degraded and require restoration to protect water and biodiversity.

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

What is the extent of riparian PPA environmental liabilities on rural properties in Southwestern São Paulo?

How do these liabilities vary by property size?

How much PPA area requiring restoration is not registered in the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR)?

Data sources

Rural property boundaries from SICAR (CAR database)

Hydrography, land-use, and PPA maps (reference year 2013)

Legal parameters from the Native Vegetation Protection Law (Law No. 12,651/2012)

Methods

Classification of rural properties by size using fiscal modules

Spatial overlay of property boundaries, riparian buffers, and land-use classes

Analysis limited to riparian PPAs (watercourse margins and springs)

Buffer widths defined by property size and legal restoration requirements

Three analytical scenarios to address uncertainty around properties without CAR registration:

- Only registered CAR properties

- Unregistered properties assumed to be very small (minimum restoration width)

- Unregistered properties assumed to be very large (maximum restoration width)

Key quantitative results

Property size distribution (by land area):

- Large properties: 62%

- Medium: 15%

- Small: 17%

- Micro-properties: 6%

Total riparian PPAs: ~155,065 ha

Degraded PPAs: ~47%

In all scenarios, more than 40% of PPAs require restoration

Large properties hold ~70% of total PPA liability

Small properties show ~50% proportional degradation of their PPAs

Estimated restoration cost: USD 76–100 million (≈ USD 2,000/ha)

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial scale: 15 municipalities in Southwestern São Paulo with sufficient CAR coverage

(not the entire Upper Paranapanema Basin)

Temporal scale: Reference year: 2020, Land-use base maps: 2013

Reference publications

Ferrari, V. M., Melo, S. R., Oliveira, M. A., & Martensen, A. C. (2021).

Passivo ambiental das Áreas de Proteção Permanentes (APPs) ripárias do Sudoeste Paulista.

Estudos Geográficos

Incomplete documentation of biodiversity

Despite its ecological importance, biodiversity in the basin remains incompletely documented. The rediscovery of the rare amphibian Phrynomedusa appendiculata in Capão Bonito after more than 40 years highlights substantial gaps in species inventories and long-term monitoring.

This finding enabled new ecological, acoustic, morphological, and phylogenetic data to be collected. It also suggests that additional species of conservation concern may remain undocumented.

UFSCAR has a range of initiatives to document species richness in the region including installing recording devices at various locations and using machine learning to rapidly identify species.

A species considered extinct for over 40 years was rediscovered in 2011 in an Atlantic Forest area. Significant portions of the basin’s biodiversity remain undocumented. Current biodiversity assessments likely underestimate species richness and conservation value, particularly in small forest fragments.

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

To what extent is biodiversity in the Upper Paranapanema Basin under-documented, and what evidence indicates gaps in species inventories and long-term monitoring?

Data sources

Targeted field surveys (e.g. amphibians, birds) conducted in selected municipalities

Species occurrence records and museum collections

Historical literature and distribution maps

Molecular, acoustic, and morphological datasets generated during recent surveys

Methods

Field surveys focused on suitable habitats (e.g. riparian forests, forest fragments) using standard herpetological sampling protocols.

Species identification based on:

morphological traits

acoustic signals (advertisement calls)

molecular analyses (DNA sequencing)

New records were compared against historical occurrence data to assess range continuity and knowledge gaps.

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted to clarify taxonomic relationships where data were previously unavailable.

Key quantitative results

The amphibian species Phrynomedusa appendiculata, considered “lost” due to the absence of records since 1970, was rediscovered in Capão Bonito.

This represents the first confirmed record in more than four decades, filling a major gap in the known geographic distribution of the species.

The rediscovery enabled the first molecular and phylogenetic analyses for this species, as well as new ecological and acoustic descriptions.

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial: Localised sites within the Upper Paranapanema Basin, particularly forest fragments and riparian habitats

Temporal: Contemporary surveys (2011–2019) compared against historical records from the mid-20th century

Reference publications

Moraes, L.J.C.L. et al. (2022).

Rediscovery of the rare Phrynomedusa appendiculata.

Zootaxa, 5087

Impacts of a changing climate

Scientific evidence indicates that climate change is altering rainfall patterns in the Alto Paranapanema Basin, with implications for water resources, agriculture, ecosystems, and infrastructure. Observed and modelled changes include shifts in the timing and amount of rainfall.

These climatic shifts matter because water availability and variability are central to the basin’s socio-ecological systems, influencing crop water demand, erosion risk, species habitats, and hydrological function.

Analysis focused on the Alto Paranapanema Basin finds temporal shifts in rainfall patterns, including a reduction in rainfall during the wet season of up to 40% compared to historical averages. These changes point to a more variable and potentially less predictable rainfall regime, with implications for water storage, agricultural timing, and ecosystem water balance.

Climate change is modifying rainfall patterns in the Alto Paranapanema Basin, reducing wet-season rainfall and increasing variability, which compounds local water and land challenges.

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

How is climate change expected to alter rainfall patterns (amount, seasonality, and variability) in the Alto Paranapanema Basin, and what are the implications for hydrological conditions in the basin?

Data sources

Historical rainfall records from meteorological stations within and around the Alto Paranapanema Basin

Downscaled climate model outputs representing future climate scenarios

Basin-scale spatial data used to aggregate and analyse rainfall patterns across the catchment

Methods

Statistical analysis of historical rainfall time series to establish baseline seasonal patterns

Application of climate change projections to assess future rainfall behaviour

Comparison of historical and projected periods to evaluate:

- changes in wet-season rainfall totals

- shifts in rainfall seasonality

- changes in interannual variability

Basin-wide aggregation of results to characterise system-level rainfall responses

Key quantitative results

Wet-season rainfall shows a projected reduction of up to ~40% relative to historical averages under climate change scenarios.

Rainfall patterns become more irregular, with increased variability between years.

The reduction is seasonally concentrated, affecting periods critical for water recharge, agriculture, and ecosystem functioning.

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial scale: Alto Paranapanema Basin (UGRHI-14), São Paulo State

Temporal scale:

- Historical baseline: multi-decadal rainfall records (20th–early 21st century)

- Future projections: mid- to late-21st century climate scenarios (scenario-based projections rather than single deterministic forecasts)

Reference publications

Hucke, A. T. S., et al. (2024).

Assessment of climate change impacts on rainfall and streamflow in the Alto Paranapanema Basin, Brazil.

Sediment production and erosion

Changes in land use and land cover in the Upper Paranapanema Basin, particularly the expansion and intensification of agriculture, have led to a sharp increase in soil erosion, sediment production, and sediment export to water bodies.

Between 1987 and 2017, sediment production more than doubled and sediment export increased substantially, reflecting the conversion of pasturelands to more intensive agricultural systems and the expansion of farming into areas with higher erosion susceptibility.

Modelling results indicate that restoring riparian Permanent Preservation Areas (PPAs) and adopting conservation practices such as terracing and no-tillage can significantly reduce both sediment production and sediment export, especially when these strategies are combined.

Climate change is modifying rainfall patterns in the Alto Paranapanema Basin, reducing wet-season rainfall and increasing variability, which compounds local water and land challenges.

Methods, data and assumptions

Research questions

How have changes in land use and land cover affected sediment production and sediment export in the Upper Paranapanema Basin over recent decades?

What is the relationship between agricultural expansion, erosion susceptibility, and sediment dynamics in the basin?

To what extent can riparian restoration and soil conservation practices reduce sediment production and export under different management scenarios?

Data sources

Historical land use and land cover maps for the Upper Paranapanema Basin for 1987 and 2017

Spatial data on topography, soils, and erosion susceptibility

Hydrological and sediment modelling inputs representing basin conditions under different management scenarios

Methods

Statistical analysis of historical rainfall time series to establish baseline seasonal patterns

Application of climate change projections to assess future rainfall behaviour

Comparison of historical and projected periods to evaluate:

- changes in wet-season rainfall totals

- shifts in rainfall seasonality

- changes in interannual variability

Basin-wide aggregation of results to characterise system-level rainfall responses

Key quantitative results

• Sediment production increased from 38.86 t ha⁻¹ year⁻¹ in 1987 to 91.80 t ha⁻¹ year⁻¹ in 2017, an increase of 136.2 percent

• Sediment export increased from approximately 1.37 t ha⁻¹ year⁻¹ in 1987 to 4.1 t ha⁻¹ year⁻¹ in 2017

• Restoration of PPAs alone reduced average sediment production to 42.69 t ha⁻¹ year⁻¹, a reduction of more than 50 percent

• Conservation practices alone reduced sediment production to 11.42 t ha⁻¹ year⁻¹, a reduction of 87.6 percent compared to current conditions

Combined PPA restoration and conservation practices reduced sediment production to 10.81 t/ha/year

Sediment export under PPA restoration decreased to 1.66 t/ha/year, a reduction of approximately 59.5 percent

Combined PPA restoration and conservation practices reduced sediment export to 0.378 t/ha/year, corresponding to a reduction of approximately 90.8 percent

Spatial and temporal scale

Spatial scale: Upper Paranapanema River Basin

Temporal scale: Land use and sediment dynamics assessed for the period between 1987 and 2017, with scenario simulations representing alternative management futures

Reference publications

UFSCAR research